- Home

- Tony Kelly

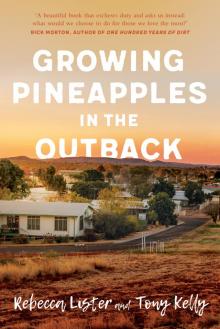

Growing Pineapples in the Outback Page 10

Growing Pineapples in the Outback Read online

Page 10

Though I despise everything about this food outlet, we head for the drive-through and buy two soft-serve cones. Such is life.

It’s Thursday night. Tomorrow Mum goes with Marlene to the aged care facility to administer a church service.

Mum tells me that most of the people who come to the service are not actually Anglicans; in fact, she suspects that most of them have very little interest in Christianity at all. She assumes, and probably rightly so, that most of the people who come are more interested in the morning tea she and Marlene provide. I sit at the table and watch Mum as she prepares her food.

When Mum first started going to ‘the home’, as she calls it, she would bake biscuits or a cake. Now, however, there are strict health and safety rules in place, and you can only take packaged food into the facility.

Mum and Marlene have a pretty good arrangement worked out. Mum buys cheese and biscuits, and Marlene buys doughnut balls from the plaza. Mum opens the packet of pre-sliced cheese and takes out each slice. She then unwraps each slice from the plastic, cuts it into biscuit-size pieces and puts them in a Tupperware container. She opens the packet of biscuits, takes them out of their wrapper and puts them into another plastic container.

‘Are you allowed to do that?’ I ask.

‘What?’

‘Open the packets and handle the food? Doesn’t that defeat the purpose of the policy?’

‘No one has ever said anything,’ Mum says.

I watch as she continues cutting the cheese and ask no more questions. When she’s finished, Mum places the two containers in the front of the fridge so it’ll be easy for her to find them in the morning.

One time she accidentally took a plastic container out of the fridge that had leftover mashed potato in it, and took that instead of the cheese. Apparently the residents were in hysterics over this, but some still chose to have the mash on their biscuits.

My phone pings; it’s Tony.

Change of plan. Some of the gang from work have invited us to join them at the vodka bar for drinks and blinis. You in?

I smile and text back:

Sounds beaut! If you get there first, order me a martini.

I look out from my desk to the lounge room; Mum is still asleep in her chair. I think about waking her up. I struggle with the fact that, in the bigger scheme of things, surely it’s not a big deal if she spends her day inside the house in a somnolent blur. She doesn’t demand anything or express any discomfort or unhappiness.

The issue, however, is that when she spends her days like this, both her mood and energy slump to such a degree that by the end of the day flatness takes a grip upon her that’s difficult to budge. It’s a small house, and if left unchecked, Mum’s grey mood can dominate. If I wake Mum, I will have to engage with her, otherwise she will remain flat and the evening will be unpleasant for her – and for us.

But I don’t feel like engaging today. I feel a bit flat myself, and I know why. Like Mum, I’ve been sitting for too long, and it’s been a long week of working alone. I need more stimulation and company. I’m pretty self-contained and adore Mum, but I know this week has been a bit too much of just the two of us. I see the change that happens in Mum after her outings. She is always far more upbeat. It’s probably the same for me; other than going to the shops and Mum’s appointments, I have very few outings.

I feel envious of Tony. His job puts him in contact with all sorts of people. Every day he has a new story about someone he’s met with or spoken to on the phone. I don’t want a lot. My life is pretty full. My Melbourne projects are keeping me very busy, and likewise my life with Mum, Tony and our extended Mount Isa family.

I’m good at working alone but I love working with other people. I like a balance between time alone and time with others, and at the moment things are weighted too heavily to the former. I need to find a small contract or some part-time work so that I can mix up my lifestyle a bit more. So far the only paid employment I’ve been able to secure was teaching a few aqua aerobics sessions at the local pool. But I’m not going to the pool at the moment as I’ve had a falling-out with the pool manager.

Actually, that’s not entirely true. I’m fine, but the manager has fallen out with me.

It surprised me because I thought we were getting on quite well. I wouldn’t have said we were boon companions, but he had employed me to do a few classes. No one would call him sanguine; in most of my dealings with him I found him to be offhand and borderline unfriendly. But I felt I was just starting to break through his tight veneer and get the occasional smile and hello.

This all changed a few weeks ago. ‘Your music is too slow,’ he told me. In the rarefied world of aqua aerobics, this is akin to a sin. The music needs to be at a certain number of beats per minute in order to match the required cardio workout.

‘What?’ I said.

‘Some of the women have complained.’

This was news to me. The feedback I’d received from the class had been to the contrary. ‘My music is industry standard,’ I told him confidently.

And with that he stopped employing me. Oh, the fickle world of aqua aerobics!

So here I am with all my fancy-pants university degrees and qualifications, but no bastard wants to employ me! It’s so sad that it’s actually funny.

But I can’t complain. In a few weeks I’ll be heading off to Melbourne again for three weeks. After a fairly torturous few months of work, I have finally finished the treatment documents for the film. My inexperience as a film writer has made it a long and hard task.

When I’m in Melbourne, HERE will open and I’ll do my development and showing of Resting Bitch Face. My play I’ll Be There with the Victorian Trade Union Choir will also have a number of shows on, and I have been engaged again as the director. We’ll also celebrate Lucille’s twenty-first birthday, so there’s a lot to look forward to.

Knowing all this makes my current lethargy feel all the more self-indulgent. I chose to be here – no one asked me to come, and no one expected me to come – so really I just have to ‘step up’ and get on with it.

Nonetheless, my lack of stable income and employment keeps me awake at night. I’m in my early fifties, don’t have a secure job, don’t own a house, have a second-hand car and am back living with my mother in a town where no one knows me, and where no one seems particularly interested in my skills.

We’re still paying rent on our place in Melbourne, and my lack of income means I am dependent on Tony. I have never earned a lot of money but, other than when our children were really small, I’ve always been able to bring in enough to pay my own way.

Mum is very generous and often wants to pay for the household’s groceries and living expenses, but Tony and I insist on going halves. I’m an expert at eking out an excellent existence on a meagre amount of money, but currently it feels very close to the bone.

I get into a conversation with a young professional at choir. I tell her how difficult it has been for me to make connections with people through my work. ‘I email people and ring them, but no one ever gets back to me,’ I say.

‘Everyone is so busy,’ she says.

‘Yeah,’ I say.

‘Once you get something here, it just takes off,’ she says. She tells me about the fast-tracking that occurred with her career once she came to Mount Isa.

‘My problem,’ I say, ‘is that no one here knows my work, so I have no one to champion me.’

‘I champion myself,’ she says.

‘Oh, I do too,’ I say, ‘but how I network and connect with people is very similar to the way I work with people. I need a point of entry, and if that isn’t there then I’m not good at talking myself up. That’s not how I work.’

‘It’s all about self-belief,’ she says, and moves on.

‘Yeah, thanks for that,’ I mutter to myself.

I start to wonder if what I

am looking for doesn’t exist. Am I naive – or, worse, selfish? I want a job that allows me to look after Mum, that has the flexibility so that I can return to Melbourne for my project work, that brings me into contact with like-minded people who value my talents, and that pays decent money. Does such a job even exist?

I’ve spent years getting my kids through school, and supporting Tony through a postgrad law degree and two federal elections where he ran for the House of Representatives with the Australian Greens. And he has spent years supporting my arts practice. We thought we were living the dream, investing in a lifestyle that would eventually reap some rewards. But now, as I sit at this desk, I wonder where it’s all going to lead.

Sometimes I feel anger towards Mum and the rest of my family for not discussing this situation. Why didn’t we talk about this? Why didn’t we make plans for Mum and her old age? Why didn’t we put things in place years ago? We are a family of avoiders. I suspect that if things had gone on as they were, Mum would have been forced into the aged care facility and that would have been that. And without doubt she would have been miserable in there.

I know that I need to get Mum up and out of her chair, and engaged in a game of Upwords or a crossword puzzle – or, better still, take her outside for some fresh air and exercise. Getting her out of her chair also means I can give it a quick clean. When she spends all day in the big vinyl chair, the whole house starts to smell slightly sour. Many years ago she famously said that she ‘loathed exercise’, but I know that getting her moving will stimulate some endorphins and improve her mood.

The truth is there are no Japanese restaurants or Spanish bars in Mount Isa, and nor is there a vodka bar. We’ve never had an invitation from ‘the gang’ at Tony’s work to join them for Friday drinks as there is no gang. He works with just one other person, a lovely woman who is much younger than us, and who is keen to get home after work to her fella and their baby.

Tony and I do the texting routine each Friday because it makes us smile and keeps at bay the nagging feeling that we are missing out on a more exciting life back in the big smoke. Who knows? Perhaps if we were back in Melbourne, we’d be having the same text messaging sequence but without the irony. That doesn’t sound like nearly as much fun! I text Tony:

Hey, how about we just have quiet one at home?

He replies immediately:

That sounds perfect. I’ll go to the bottle shop and get some beers and a bottle of wine.

I write back:

And some of those new gourmet chips … Mum loves them!

We both know I’m the one who loves chips the most.

From my window I can hear Shawn, Cheyenne and baby Jaydon talking and laughing as they head to the park with Maleka. I’m tempted to call out to them, but I don’t want to interrupt this moment in which they look so happy and content.

I go to my room and put on my new pineapple muu-muu that my friend Beverly has made and sent to me. It is bright green with large brown, yellow and green pineapples on it. It screams ‘relaxation’! I run a comb through my hair, wash my face, and put on a bit of lippy and a pair of shiny earrings. I walk to the lounge and gently wake Mum.

‘Where are you going?’ she asks.

‘Here,’ I say.

‘Here?’

‘Yes. We’re having drinks when Tony gets home.’

Mum nods and smiles. She gets up and shuffles to her room. I hear doors opening and shutting and the tap being turned on and off. After a short time Mum comes back into the lounge wearing a fresh muu-muu. She too has washed her face and combed her hair. We smile at each other and head outside.

I lead Mum around the backyard and we look at all the new plants Tony and I have put in. Lots of the native bushes are in bloom. Mum gets very close so that she can see them. ‘The lorikeets and rosellas will love these,’ she says.

I take her down to the back of the garden and show her the pineapple and aloe vera plants I’m putting in.

‘Are you planning on planting out the whole backyard with pineapples?’ she asks.

‘Maybe,’ I say.

‘They’re bromeliads, aren’t they?’ she asks.

‘Yes,’ I say.

We walk around to the front and she looks at my frangipani cuttings in the pots. ‘Put them in the full sun for a few days,’ she says. ‘It might dry them out.’

While she does her stepping exercises up and down the front steps, I move the pots into the sunshine.

When Tony gets home, he brings drinks and chips out to the verandah. Mum and I sit and watch him water the garden. Soon we’ll cook dinner together. Fish and salad has become our Friday-night specialty. Tony has picked up fresh barramundi, caught in the Gulf of Carpentaria and sent down to the fish shop at the ice works. Mum has said she’ll make the salad. She is bright and chirpy.

After dinner we might sit on the verandah and listen to music, or maybe we’ll play a game of Upwords. Tomorrow is Saturday, and I think about going to a garage sale or having a spin around Kmart. There are so many possibilities ahead.

6

Tables Turned

Tony

Bernice picks me up at 8 am to take me to the hospital for my hernia operation. A couple of snips in my abdomen, poke the intestine back through the abdominal muscle, stitch me back up and I’ll be done.

‘I should be right for the board meeting at six this evening,’ I tell her. ‘I’ll text you when I’m done and you can pick me up.’

This meeting with one of the native title groups has taken months to organise, and I’m adamant that it should go ahead, and that I should be there.

‘We’ll see,’ says Bernice.

I nod to the young Aboriginal man in his pyjamas smoking near the entrance. He has a patch over one eye, and is trailing a drip trolley. He gives me a smile.

I got the hernia six weeks ago, just before a bushwalking trip on Hinchinbrook Island with members of my family. I wasn’t going to pull out – the trip had been six months in the making. Despite getting clearance from my doctor, and some anti-constipation drugs – ‘Avoid straining at all costs,’ he warned – I spent the five days hiking down the eastern flank of the island in perpetual fear of my abdominal muscle locking off around my lower intestine, which would result in me being airlifted off the island.

But my fear was mild in comparison to my friend Brad’s. After my daughter Lucille realised she couldn’t come on the trip, I offered the vacancy to Brad. ‘You’ll be the only non-Kelly,’ I told him. He took up the offer regardless.

Brad had recently been diagnosed with melanoma, and was keen to walk the island again while he still could. It wasn’t until we were well into the hike that I understood how unwell Brad was. Normally he would be up front blazing the trail, exploring side routes and skylarking around. On this trip he hung well back, often bringing up the rear. He never gave up but I knew he was struggling. At nights he tossed and turned in a lather of sweat as his heavy-duty medication coursed through his veins, and would wake up agitated and drained.

I was also worried about my oldest brother, Martin. He had not long ago recovered from a heart attack, and was susceptible to atrial fibrillation. He too had been given the all-clear by his doctor, but on the long, hot walk up from Zoe Bay, Martin alerted us to the fact that he was ‘in AF’. I had a satellite phone at the top of my pack and made sure I was close to him as we plodded slowly up the spur. That was the last big day of walking, and it was with enormous relief that we made camp in good health that night.

Despite these medical anxieties, the trip was amazing and I felt extremely lucky that I had the opportunity to do it. Beck had wanted to come but couldn’t. When making the decision to come to Mount Isa, one of the things in our ‘plus’ column was the promise of lots of weekends away together – trips out bush with the swag, sorties to the gulf and the like. But the reality had been much different. Diana tried respite once

and didn’t like it, and she wasn’t keen to go back, insisting that she was fine to look after herself. Beck concluded that we could leave Diana home alone for a couple of days but no more, and only if the nieces were able to call in daily.

On the way to Hinchinbrook, I had had the opportunity to see my brother Paul and nephew Dan play at a drought-relief concert organised by my cousin. Beck was able to slip away for two nights and join me.

We drove through Kynuna, in the Channel Country south of Cloncurry. It was here in 1991, stranded in floods for five days and camping on the floor of some old shearers’ quarters, that we had decided to get married. The shearers’ quarters were still standing, but only just. They were extremely dilapidated and stood forlorn, surrounded by a falling-down rusty fence, red dirt and weeds. Surprisingly, there was a ‘For sale’ sign hanging off the fence, creaking in the breeze. Beck posted a picture on Facebook with the tagline: ‘In this building we decided to get married over 30 years ago. Now we are going to buy it, do it up and move here. Full circle.’ It wasn’t meant to be taken seriously, and most people who know us would know that we’re not the ‘doing up’ type. Our idea of renovating is plonking an old caravan in the backyard and running out an extension lead from the laundry, which is what we did when Beck’s nephew Brian came to live with us in Daylesford fifteen years earlier. Within minutes, though, Beck’s phone was lighting up with congratulatory posts: ‘Awesome! … Great news! … Go Beck and Tone!’ There were some alarmed ones too: ‘Are you kidding? Don’t do it!’

We arrived in Longreach well in time for the concert, which was to take place on the grass outside the Hall of Fame. The show, which included support from Troy Cassar-Daley, was fantastic. My sister Anne was there as well, and our cousin and his family and friends treated us like royalty – until I mentioned my work.

‘So you’re Paul’s brother?’ one fella in moleskins, a Wrangler shirt and R.M. Williams boots asked backstage.

Growing Pineapples in the Outback

Growing Pineapples in the Outback